Two English officers see the American Civil War

Henry Charles Fletcher of the Scots Fusilier Guards (now Scots Guards) in November 1862, in just a few weeks travelling largely by rail, covered an immense distance through the Southern States. It was not Fletcher’s first visit to the country, for in the spring of 1862, as a foreign observer, he had been with the Federal Army of Major General George Brinton McClellan during the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia. That visit went largely unrecorded. However the second visit was recorded and appeared in the Cornhill Magazine in mid 1863.

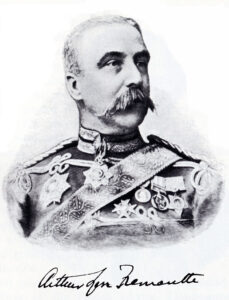

Arthur James Lyon Fremantle of the Coldstream Guards, is one of the best known foreign military observers of the civil war. Although he was never an official observer rather more a tourist, Fremantle was even depicted in the film Gettysburg. His diary was published later in 1864 and became a best seller. He entered the South by crossing the border from Mexico over the Rio Grande River to Brownsville Texas.

In just over three weeks he had reached San Antonio travelling on horseback, on mules and wagons often sleeping on the ground with some unwelcome companions as his entry for 15 April shows: ‘ I slept well last night in spite of the ticks and fleas…’ He found San Antonio a ghost town as: ‘All the male population under forty are in the military service.’

Whereas Fletcher’s journey south along the Mississippi River on the steamer Rowena was more comfortable, on board was a surprising mixture of people. ‘My fellow travellers consisted principally of officers and soldiers (Federal) going to several posts on the Mississippi River.’ There were also many ‘…traders or sutlers with contracts to supply these troops, or hoping to make some money by an illicit traffic in cotton.’ The biggest surprise was to see thinly ‘…disguised Confederate Officers’ who had been north to see friends and were returning south to join the Rebel Armies.

Once his fellow passenger found out Fletcher was English he was subjected to their political views which ‘…inclined to the Confederate side, for most of the employees on board these Mississippi steamers are “Secesh” (secessionists). Meals on board, he found a ‘scramble’ while the passengers seemed to pass most of the time by ‘…drinking at the bar, playing poker and spitting.’

In late November he reached Memphis, part of which had been turned into a Federal fortified camp where he saw ‘…some particularly raw troops being licked into shape.’ He obtained a pass to cross the Federal lines from the then Major General William Tecumseh Sherman.

On the 14-15 May 1863 Fremantle crossed the Mississippi evading the patrols of Federal gunboats. He crossed the river in a skiff containing ‘….eight persons, besides a Negro oarsman named Tucker.’ They passed through a large swamp and were often ‘…obliged to get into the water up to our middles to shove.’ Water that was ‘teaming’ with snakes and alligators, the weather he found ‘…most disagreeable, either burning sun or a downpour of rain.’ It took them eleven hours to cover 28 miles. After which they reached Vidalia on the Louisiana bank of the river opposite Natchez. There in an Inn he enjoyed the luxury of a bed, ‘…all to myself, which enabled me to take off my clothes and boots for the first time in ten days.’

Having crossed the lines in a small party Fletcher found himself in Hernando where he spent the night in a small inn. Shown to his room it contained ‘…three beds, but already five people occupied them, one, a particularly dirty but civil guerrilla, was sleeping in the half bed allotted to me.’ Fletcher declined the bed spending the night in a chair by the fire.

Much of Fletcher’s journey was by train although he found the system in poor repair ‘…the rails are scarcely in a fit state to be travelled over and the engines are often out of order.

Reaching Jackson the capital of Mississippi he found, in its ‘…two or three wide streets’ a few shops open where ‘…the prices of the commonest articles was enormous.’ He paid half a dollar for some soap and over two for a toothbrush.

Six months later Fremantle reached Jackson, the town by then much changed. The four railroads leading to the town had been destroyed by Grant’s troops in their attempt to take Vicksburg so he arrived on foot having to walk the last three miles into the town finding: ‘All the numerous factories had been burnt down by the enemy, who were of course justified in doing so, but during the short space of thirty-six hours, in which General Grant occupied the city, his troops had wantonly pillaged nearly all the private houses.’

Fletcher went onto the Gulf Coast reaching Mobile Alabama which was much warmer and he found: ‘Oranges were growing in the open air.’ While there he was introduced to Admiral Franklin Buchanan who took him on board CSS Ovieto the ship built in Glasgow. Fletcher was surprised to find many of the crew were ‘Englishmen’ willing to serve the Southern cause.

Fremantle also travelled to Mobile where he was shown the city’s defence by General Slaughter consisting of a series of Forts. He found out that: ‘Blockade-running goes on very regularly at Mobile. The steamers nearly always succeed but the schooners are generally captured.’

From Mobile their paths diverged, not only in time but direction although both travelled to Montgomery, first Fletcher heading onto the Atlantic coast. While Fremantle went north via Atlanta and then onto Chattanooga Tennessee arriving on the 28 May.

A few days later Fremantle found what he was looking for at Shelbyville, General Braxton Bragg commander of the Army of Tennessee. He had heard that Bragg was not overly popular with his troops. Fremantle described him as being, ‘very thin’ and that: ‘He stoops, and has a sickly cadaverous, haggard appearance….. bushy black eyebrows….and a stubby iron-grey beard, but his eyes are bright and piercing. He has the reputation of being a rigid disciplinarian.’ However Fremantle found him ‘…extremely civil’ and Bragg gave him permission to visit any part of the army.

There he met the colourful Colonel St. Leger Grenfell, Englishman and soldier of fortune calling him ‘…one of the most extraordinary characters I ever met.’ At that time he was Inspector of Cavalry to Bragg’s Army. He had previously served with the famed Confederate raider John Morgan.

Three days after leaving Mobile Fletcher reached Charleston and he ‘…had the pleasure of passing the evening…’ with another leading Confederate General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard whose job it was to defend the town. However Fletcher was keen to get to Richmond and explore the old battle-fields of the Chickahominy where six months before he had been an observer with the Federal Army of the Potomac. He was on the train to Wilmington within a day but missed his connection at Weldon North Carolina which he described as ‘…one of the most miserable places I ever saw…’ Yet he was fortunate in having a bed to himself in one of the ‘…dreary houses, dignified by the name hotels…’

The next day he reached Richmond and found the city busy with ‘…traffic in the streets, the theatres are open, ladies riding and driving…’ But there were few troops around, rumour said they were at Fredricksburg where a battle was expected. Hiring a ‘…a wretched horse…’ he set off for the battlefields.

‘Across the deserted fields, the former stations of the Confederate pickets, I made my way, then through the abandoned Federal camps and entrenchments, and through the woods, and among the numerous graves of those who fell at Fair Oaks and The Seven Days battle. The country was deserted; a solitary sportsman looking for partridges was the only person I encountered.’

He found that the countryside showed the ‘…palpable signs of war, fences broken down and destroyed, houses burnt; in short a fertile country had become waste.’

Fletcher was soon off north again he reached Washington by steamer from Alexandria, it was snowing and he was still using the permit issued to him in Memphis and signed by General Sherman. He ended his account with. ‘Thus terminated my rapid two months travelling through the Confederate States…’ He was convinced ‘…that no danger will ever frighten, or bribes of power induce, the States of the Confederacy to join again the Northern Union.’

Fremantle having been with one of the main Confederate field armies set off in June 1863 to find the other main force, the Army of Northern Virginia. On 21 June he caught up with the army on the march north in the Shenandoah Valley at 8.30 in the evening ‘…Pender’s division encamped on the sides of hills, illuminated with innumerable campfires, which looked very picturesque.’ He was being chaperoned as he called it by a Sergeant Norris, they found shelter in a barn that night. ‘We turned our horses into a field, and found our hayloft most luxurious after forty-six miles ride.’

The next day he was able to view Pender’s men on the march: ‘The soldiers of this division are a remarkable fine body of men, and look quite seasoned and ready for any work. Their clothing is serviceable, so also their boots, but there is the usual utter absence of uniformity as to the colour and shape of their garments and hats, gray of all shades, and brown clothing with felt hats, predominate.’

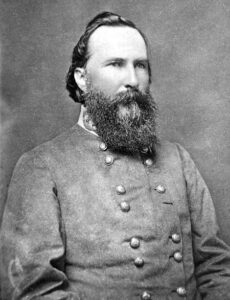

Six days later he was with the 1st Corps commanded by General James Peter Longstreet’s who he described as ‘…a thick-set determined looking man…’

On 30 June Longstreet introduced Fremantle to the commanding General Robert E. Lee, he was impressed. Finding Lee ‘…almost without exception, the handsomest man of his age I ever saw.’ Fifty-six years old at the time Fremantle went on: ‘He is the perfect gentleman in every respect. I imagine no man has so few enemies, or is so universally esteemed.’

Fremantle would witness the three day battle of Gettysburg he noted on 1 July: ‘At 4.30 pm we came in sight of Gettysburg, and joined General Lee and General Hill, who were on the top of one of the ridges which form the peculiar feature of the country around Gettysburg. We could see the enemy retreating up one of the opposite ridges, pursued by the Confederates with loud yells. The position into which the enemy had been driven was evidently a strong one.’

The battle developed into an attempt by Lee to drive the Federals off the high ground which would prove a costly mistake. On the third day he witnessed the retreat of Confederate troops after what became known as Pickett’s charge at first coming upon Longstreet he thought he was in time to see the attack: ‘I remarked to the General that “ I wouldn’t have missed this for anything.” Longstreet was seated at the top of a snake fence at the edge of the wood, and looking perfectly calm and unperturbed. He replied, laughing, “The devil you wouldn’t! I would like to have missed it very much; we’ve attacked and been repulsed: look there!”

At last Fremantle had a clear view of the battlefield even to the Federal positions on Cemetery Ridge ‘…and saw it covered with Confederates slowly and sulkily returning towards us in small broken parties, under a heavy fire of artillery.’

Realising his leave would soon be up on 7 July he left the Army of Northern Virginia travelling north for New York and a ship to take him back to England. Six days later he was in New York coming upon the draft riots that had consumed the city near his hotel: …I perceived a whole block of buildings on fire…’ there were soldiers on the streets trying to restore order the mob wanted to lynch all Negroes. Fremantle asked a ‘…bystander what the Negroes had done that they should want to kill them? He replied civilly enough-“Oh sir, they hate them here, they are the innocent cause of all these troubles.’

Like Fletcher, Fremantle was convinced that the North would be unable to ‘subdue’ the Confederate States.

How could Fremantle and Fletcher have got it so wrong? The 1954 edition of The Fremantle Diary was edited by Walter Lord, in his postscript he felt Fremantle had fallen ‘…under the spell of frontier days, rattling trains, river boats, campfires and close escapes.’ And he was ‘…in love with the South, and his heart ruled his mind.’ I suspect Fletcher felt much the same and sided with the under-dog.

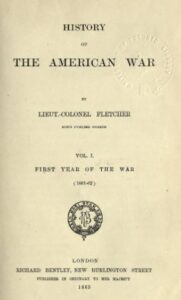

Fletcher’s three volume history of The American War published by Bentley in 1865-66 was not well received. In 1872 he became private secretary to the Governor of Canada Lord Dufferin. He returned to his regiment in 1875 but retired in 1879 through ill-health and died the same year aged only forty-six.

Fremantle’s book Three Months in the Southern States was published in 1864 based on his diary, it was well received on both sides of the Atlantic and even printed in Mobile so Southerners could read how they were perceived by a foreign visitor.

Fremantle rose to the rank of Major-General and commanded the Brigade of Guards at the battle of Tamai in 1884. In 1894 he was appointed Governor of Malta and was popular in the post. He was awarded the Knights Grand Cross of the order of St. Michael and St George and the Companion of the order of Bath. He died in 1901 aged sixty-five.

The journeys of Fletcher and Fremantle along with others are more fully explored in my book Memories and Echoes.