‘Operation Judgement’.

‘During the attack a hundred thousand rounds were fired at us but only one aircraft was shot down in each wave. I got hit underneath by one half-inch machine gun bullet. It was the pilot’s job to aim the torpedo. Nobody was given a specific target. I dived down in between the moored ships aimed at the nearest big one, which turned out to be the Littorio, and released my torpedo. While you’re low down over the water and surrounded by enemy ships the comfort is that they can’t shoot at you without shooting each other. I then made for the entrance to the harbour at zero feet and thence back to Illustrious’. So wrote Lieutenant Michael Torrens-Spence, Swordfish torpedo-bomber pilot, about the Fleet Air Arms raid on the Italian fleet at Taranto in November 1940.

Italy had entered the Second World War in June 1940, an event the New York Times clearly laid at Benito Mussolini’s feet. ‘With the courage of a Jackal at the heels of a bolder beast of prey, Mussolini had now left his ambush. His motives in taking Italy into the war are as clear as day. He wants to share in the spoils which he believes will fall to Hitler, and he has chosen to enter the war when he thinks he can accomplish this at the least cost to himself’.

On the day Mussolini, the Duce, announced war, Count Galeazzo Ciano, his son-in-law and minister of Foreign Affairs wrote in his famous diary; ‘The news of war does not surprise anyone and does not cause much enthusiasm. I am sad, very sad. The adventure begins. May God help Italy’.

The Italian General Staff convened at the Palazzo Venezia in Rome a few days earlier, had warned Mussolini that Italy was ill-prepared, and the war must be short. At the time, many in Italy, although mistrusting Hitler and Germany, felt they were opportunists entering a short victorious war for profit.

Although Italy had a central position in the Mediterranean and a powerful fleet and air force, Mussolini’s attempt to make the sea ‘Mare Nostrum’ our sea, soon began to unravel.

Quickly the British Royal Navy had begun to dominate the sea from its bases at Gibraltar, Malta, and Alexandria, the Mediterranean Fleet under the command of Admiral Andrew Brown Cunningham, known affectionately as ABC, had been trying to draw the Italian battle fleet into action. However it had remained obstinately in port most of the time, and usually out of range when they did proceed to sea.

However large numbers of the Regia Navale were often concentrated at Taranto, offering a good target if the strong defences could be overcome. The Raid on Taranto, as it has become more popularly known, was a plan that had been about for several years. Born in 1935 when Italy had invaded Abyssinia, the C-in-C Mediterranean Fleet at the time was Admiral Sir William Wordsworth Fisher, under him plans were made to use aircraft from the carrier HMS Glorious to attack the fleet at Taranto, but at the time Britain took no action against Italy. During the next five years the carrier squadrons became highly proficient at night flying. Captain Lumley St.George Lyster, who became one of the main stays of the Fleet Air Arm developed the plan further in 1938.

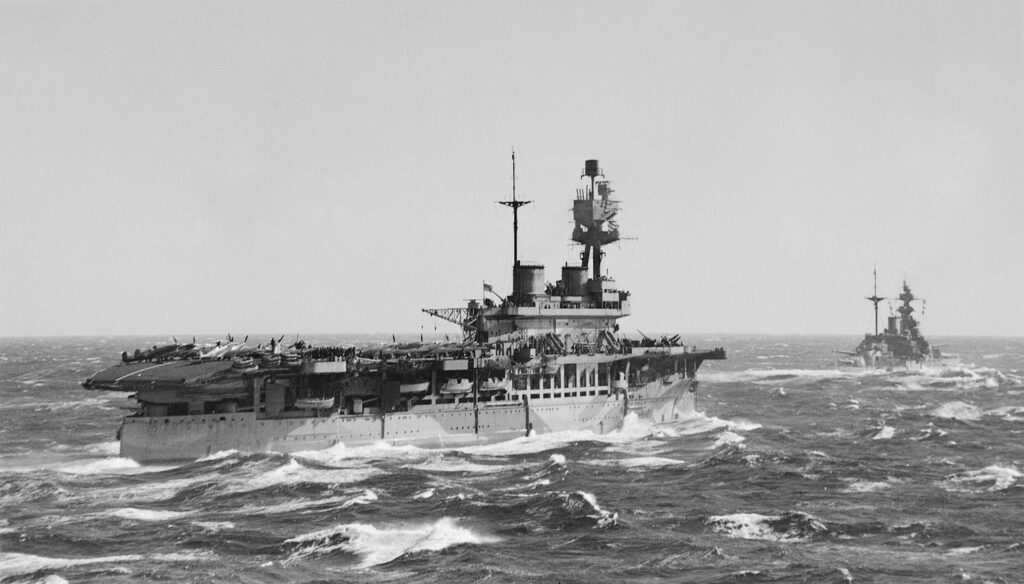

In 1940 Lyster had arrived with the new 23,000 ton carrier HMS Illustrious in the Mediterranean as Rear Admiral Carriers. Cunningham wrote of his first meeting with him; ‘At our first interview he brought up the matter of an attack, and I gave him every encouragement to develop the idea’.

So ‘Operation Judgement’ was born. Reconnaissance flights over Taranto were increased providing photographs of the harbours and defences. Both carriers of the Mediterranean Fleet, the new Illustrious and old Eagle were to be used, the operation was set for 21 October, the anniversary of Trafalgar Day, although the fact it was a moonlit night was more important. Illustrious was the class leader of six aircraft carriers and was markedly different to the carriers that had gone before. She was heavily armoured on her flight deck and on the hanger deck displacing 23,000 tons under full load 28,000 tons with a speed of thirty knots, later ships in the class would be larger. The Royal Navy at the time had the best design of aircraft carriers available. With their armoured flight decks able to withstand far more punishment than designs in service with the United States Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy, although they carried fewer aircraft and those aircraft were outdated. Illustrious brought another advantage to Cunningham’s fleet; she had the best radar of any ship in the fleet.

It was almost as if once the date of the operation was set the fates turned against the Fleet Air Arm. The Swordfish aircraft had to be fitted with long range tanks, to reach Taranto while keeping the carrier out of harm’s way, which were fitted into the middle cockpit thus reducing the crew and moving the observer to the rear cockpit, where he would combine his roll with that of rear gunner.

While this modification work was being carried out on Illustrious a fire broke out, the sprinkler system using salt water on the hanger deck saved most of the aircraft, but two were burnt-out, while five others were damaged by fire and salt water from the sprinklers. All aircraft had to be stripped down, rebuilt, after being cleaned with fresh water. Even though many members of the squadrons and ships compliment turned to, to help with the work, there was no alternative but to postpone the raid to 31 October which would be more difficult without moonlight. It was only realised days before the raid was due that it would now depend much more on light from flares. So it was postponed again to the next moonlit night 11-12 November.

On 4 November more bad luck struck the operation while escorting convoys the Eagle suffered numerous near misses in an Italian bombing raid, this led to breakdowns in the ships aviation fuel systems, and her ageing boilers were troublesome. Further delays were out of the question with winter weather approaching. Like many of the Royal Navy’s ships Eagle was old and due to operational demands long overdue a refit. Without Eagle it now meant twenty-four aircraft would be available instead of thirty, this included six aircraft transferred from Eagle to Illustrious.

Charles Lamb recalls the final briefing for the Swordfish crews on board Illustrious. ‘…in the wardroom a large scale map of Taranto and a magnificent collection of enlarged prints of the photographs I had brought from Malta was pinned to cardboard backings and on display. It was possible to study every aspect of the harbour and its defences, and the balloons, and, of course all the ships in detail’. All the Italian capital ships and some of the heavy cruisers were protected by anti-torpedo nets, hung from booms, shielding the ships to the keels. However the torpedoes carried by the Swordfish were fitted with Duplex Pistols, a magnetic device which would normally explode on contact or could be activated by the ships magnetic field. The torpedoes to be used where set to pass under the hulls avoiding the nets and exploding there.

The use of torpedoes made the operation hazardous forcing the aircraft to come in low. The dropping area was known to be restricted by balloons, for this reason no more than six torpedo bombers were to be used at a time. The attack would be formed in two waves an hour apart. In each wave there would be two aircraft dropping flares to the east of the anchorage to light up the battleships. Also more a diversion, bombing attacks would be made on the inner harbour.

However the bad luck had still not deserted them. Swordfish aircraft maintained reconnaissance patrols over the fleet in particular on the lookout for enemy submarines as the fleet steamed west. On 10 November one of 819’s Swordfish, an Illustrious aircraft, engine cut out twenty miles from the ship. The pilot tried to glide the aircraft back to the carrier but it was too far and the plane ditched in the sea. Both men were picked up. One aircraft suffering engine failure was not that unusual, but the next morning another suffered the same fate. It was quickly found one of the ships aviation fuel tanks had been contaminated by sea water, probably due to the hanger fire and use of the sprinkler system. All aircraft to be used on ‘Operation Judgement’ had their fuel systems drained and refuelled. By late afternoon of 11 November the latest photographs of Taranto were flown to Illustrious, they showed five battleships in the outer harbour, and a flying boat had reported a sixth entering. Illustrious was about 200 miles from the target when Fulmar fighter aircraft from the carrier shot down two Italian spotter planes which might have raised the alarm but did not. No doubt surprised by the fighters directed on to them by the carriers radar.

Admiral Cunningham from his flagship, the battleship Warspite, signalled Illustrious about 18:00hrs, with her cruisers and destroyers to proceed with ‘….orders for ‘Operation Judgement’…Good luck then to your lads in their enterprise. Their success may well have a most important bearing in the course of the war in the Mediterranean’.

Two hours later Illustrious was forty miles, 270 degrees, from Kobbo Point, Cephalonia, and 170 miles from the target. Shortly before 20:30 the first wave of Swordfish from 813, 815, and 824 squadrons led by Lieutenant–Commander Kenneth Williamson started lumbering off the flight deck of Illustrious, now turned into the wind with their heavy loads clawing at the air to gain height.

Williamson led them up into the cloud at 4,500 feet, he emerged into clear moonlight to find he had lost four aircraft, he was not overly concerned, it was accepted they would make their own way to the target ninety minutes flying time away.

The second strike led by Lieutenant-Commander J.W. ‘Ginger’ Hale CO, of 819 squadron took off an hour later. His flight was reduced to eight aircraft, due to the fuel problems, five were armed with torpedoes the others with bombs and flares. Charles Lamb’s aircraft L5B a flare dropper from fifty miles out he could see the lights from the harbour. ‘The sky over the harbour looked like it sometimes does over Mount Etna, in Sicily, when the great volcano erupts. The darkness was being torn apart by a firework display which spat flame into the night to a height of nearly 5,000 feet’. Just before 23:00 the flare droppers and bombers of the first wave left formation for their tasks, all aircraft had rendezvoused at the target. The torpedo bombers peeled off to the westward for their final approach. The two sub-flights of three came in toward the anchorage across Cape Rondinella and San Pietro Island, dropping down to thirty feet skimming across the water. Anti aircraft fire flashed toward them from shore batteries and the ships. The moon was three-quarters full, and to the east flares were brightly illuminating the battleships ahead.

The leading aircraft flown by Williamson L4A attacked the southernmost battleship the Cavour, his torpedo struck home, the aircraft badly damaged crashed into the water near the floating dock. His observer Lieutenant Norman J. Scarlett wrote. ‘We put a wing tip in the water. I couldn’t tell what happened next. I just fell out of the back into the sea. We were only about 20ft up. I never tie myself in on these occasions. The old Williamson came up a bit later and we hung about by the aircraft which had its tail sticking up out of the water. Chaps ashore were shooting at it. The water was boiling so I swam off to a floating dock and climbed aboard that. We didn’t know we’d done any good with our torpedo’. The second flight hit the battleship Littorio under the starboard bow and minutes later she was hit again on the port quarter. The other torpedoes from the first wave missed, exploded prematurely or failed to go off. The flare dropping aircraft having completed their primary task switched to bombing the oil storage tanks, while other bombers swooped on the ships in the inner harbour cruisers and destroyers, where they were moored sterns against jetties.

The second wave arrived over the target about midnight. The approach of their torpedo bombers was the same. The five torpedo bombers came in and hit the Duilio on the starboard side and hit the Littorio again, a fourth hit on this ship failed to explode.

Lieutenant Torrens-Spence Swordfish L5K headed towards a line of barrage balloons deep inside the Mare Grande to find a target, Lieutenant A.W.F ‘Alfie’ Sutton his observer recorded.

‘Everything seems to be coming at us stabbing groups of fire pouring up tracer….Down, down we plunge….We’re nearly at sea level suddenly Torrens-Spence pulls us up, that terrific jolt that comes at the end of a dive. We’re too short; we’re ended up away from the battleships’. They fly around the harbour looking for a target eventually they attack the Littorio. ‘We’re coming in on her beam; we’re in a terrible mass of cross-fire-cruisers, battleships, shore batteries, the lot….But we’re low, too low for the enemy gun-aimers. The place stinks of cordite and incendiaries and burning sulphur. Everywhere is wreathed in smoke, thick, choking, foul stuff. Torrens-Spence holds us low. He steadies. He cries ‘firing’.‘There’s a pregnant pause. Nothing happens. The torpedo does not come off the magnetic release has failed. He frantically recocks’. They try again, at last getting the torpedo away; L5K goes right down to sea level, even putting the wheels into the water with a crash. ‘Torrens-Spence is a brilliant pilot he retains control he flies the machine out of the water. Ahead I see the mooring rafts of barrage balloons two of them. I con my pilot between these two, and then we point towards the moon as we try to make our escape’.

The Vittorio Veneto and the heavy cruiser Gorizia were attacked but escaped unscathed. The Italians, as Lieutenant Torrens-Spence indicated, had a great dilemma firing at aircraft only thirty feet above the surface of the harbour which meant for certain hitting their own ships and the town and harbour facilities of Taranto. Generally they lifted their angle of fire. Had they maintained fire at water level it is possible few aircraft would have reached their targets, instead of only two being shot down.The first wave less one aircraft arrived back on board Illustrious four and a half hours after taking off. The one aircraft lost was that of their leader Williamson, who with his observer was taken prisoner. By 3am the second wave less one aircraft was back, E4H was lost shot down attacking the cruiser Gorizia. Lieutenants A. Bayley and H.J.Slaughter were both killed when their aircraft blew up.

During the next day, 12 November, Italian aircraft tried to locate the British fleet, and in particular Illustrious. Some of these aircraft were shot down by the carrier’s Fulmar fighters, the Italian aircraft failed to find any ships.

Air reconnaissance over Taranto showed the Cavour beached. The Littorio and Diulio were seriously damaged. It looked like two cruisers had been hit by bombs. The first Supermarina, the Italian Naval High Command, had known of the raid was when they received frantic telephone calls from Taranto. Commander Marc Bragadin was on duty in the operations room in Rome that night. ‘Bulletin followed on bulletin. It seemed that a great naval battle had lost, and no one yet knew if and when it would be possible to recover from the grave consequencesof it’.

Salvage work was quickly underway at Taranto, Littorio and Diulio were seriously damaged but both ships were repaired and ready for sea by May 1941. The Cavour took until July 1941 to be refloated, and then she was towed to Trieste for repair, but this had not been completed by the time of the armistice with Italy in 1943.

The main objective of the British attack had been successfully achieved. Half the Italian battle fleet had been put out of action albeit temporarily. Illustrious soon rejoined the fleet to be welcomed by a signal from the flagship. ‘Illustrious manoeuvre well executed’.

The Taranto raid made a profound impression around the world, here was proof that a fleet was not safe in harbour. The effects on the balance of power in the Mediterranean were immediate, for all major Italian warships left Taranto for more secure ports on the west coast of Italy, thus reducing the threat to British convoy routes through the Mediterranean and to Greece.

Winston Churchill announced to the House of Commons that the Fleet Air Arm had ‘….annihilated the Italian Fleet forever’. Something of an exaggeration but it was one of Britain’s first victories and a welcome boost for morale.

Fairey Swordfish the Stringbag.

Mainstay of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm during the early years of World War II was the Fairey Swordfish aircraft, first flown in 1934 and entered service in 1936, it was a jack of all trades with six roles; reconnaissance, spotting ffor the guns of the fleet, convoy escort-anti submarine, torpedo strike aircraft, dive bombing and mine laying. Swordfish were powered by a single Pegasus engine providing 690hp. It carried a crew of three, each in his own open cockpit, pilot, observer, and in the rear cockpit the telegraphist air gunner. Range was about 450nm but this could be increased with additional fuel tanks to about 900nm. Armament consisted of two Vickers Machine guns. One fired by the pilot through the propeller World War one style, the other used by the rear gunner. A variety of ordnance could be carried, something for every occasion, a single 18inch MK XIIB 1,620lb torpedo, four 250 lb depth charges, 5001b or 2501b bombs up to 1,5001bs, or six rockets. The maximum speed was 125 knots although few pilots managed this, in normal level flight something around 90 was a normal cruising speed.

It was from the variety of ordnance the Swordfish could carry that coined its affectionate nick-name Stringbag, when a test pilot observed; ‘No housewife on a shopping spree could cram a wider variety of articles into her string bag’. The Stringbag was sturdy and robust and able to fly with a high degree of damage, her pilots liked the manoeuvrability of the aircraft and its easy night flying qualities.

The Fairey Swordfish served throughout the war. Along with the Raid on Taranto the other great accomplishment of the Swordfish was when one from the Carrier Ark Royal damaged the German battleship Bismarck, slowing her down enough to be sunk by following British battleships in May 1941.

Taranto and Pearl Harbour.

Many people have come to believe that the Taranto Raid in November 1940 was somehow the basis, the blueprint, for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour. However this is far from the truth. The Imperial Japanese Navy had war-gamed the attack on Pearl Harbour long before ‘Operation Judgement’ took place.

There were of course many differences, the main ones being, Britain and Italy were already at war; Japan and the United States were not at war on 7 December 1941. Taranto was attacked at night, Pearl Harbour early in the morning but in broad daylight.

However it is certain that the Taranto raid further convinced the Imperial Japanese Navy the attack on Pearl Harbour was feasible. Also undoubtedly they learned of its details from the Italians. It further proved torpedo nets did not offer great protection for ships, although the Japanese did not have the advantage of the Duplex pistol in their otherwise fine torpedoes. Also their dive-bombers would be more important in their attack as the American battleships were double berthed on Battleship Row. Like Taranto concerns over the secrecy of the operation were to prove largely groundless.

The Japanese had a major advantage over the Royal Navy in the size of their strike. The attack had six carriers with 423 aircraft between them of which 353 would take part in the raid of modern design. At Taranto there was one carrier with twenty-one obsolescent biplanes.

Due to the distance involved discovery was more a worry for the Imperial Japanese Navy. Fortunately for long periods they were hidden by tropical storms. The Royal Navy operating in and around the toe of Italy was not unusual, so the Italians were not unduly alarmed and lulled into a false sense of security.

As at Taranto the attack on Pearl Harbour was made in two waves. Fighter aircraft accompanied the Japanese strike aircraft, as the Americans were expected to put up their own fighters in defence. The Japanese second wave did not include torpedo-bombers as they were seen to be highly vulnerable in their sea level approach to anti-aircraft fire once the defences were alerted.

Unlike Taranto the Japanese attack failed in its main objective changing the balance of power in the Pacific, and Pearl Harbour remained the US Pacific Fleet’s operational base. Whereas the Italians moved their battleships and cruisers out of Taranto, to bases further north and west, and the Royal Navy gained a moral ascendancy in the Mediterranean that even with the severe trials ahead it would never lose.

The raid on Taranto is covered in my book ‘The Battle of Matapan 1941.’